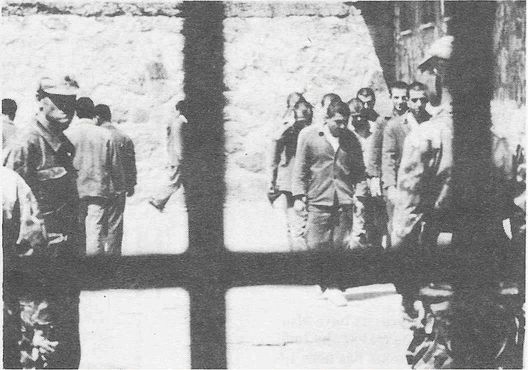

Cover picture (click on it to enlarge)

Students being arrested in Istanbul

in April 1988. A number of students have recently been arrested and interrogated

under torture.

Over a quarter of a million people

have been arrested in Turkey since 1980 on political grounds and almost

all of them have been tortured.

Thousands are now in jail. Some

were convicted for no more than expressing their opinions, many others

because they confessed to crimes of which they were innocent to escape

the agony of torture.

Most of these prisoners did not

receive a fair trial. Some were sentenced to death. Today almost 200 people

await a decision on whether they will go to the gallows.

Turkey was under martial law for

over three years. Military rule began to be phased out at the end of 1983

and it has now been lifted entirely. But human rights violations remain

widespread.

The military have seized power repeatedly

in Turkey during the last three decades, most recently in September 1980.

Unprecedented political violence

had erupted throughout Turkey in the late 1970s. Over 5,000 people were

killed. Most were members of left-wing or right-wing political organizations,

then engaged in bitter fighting. The most militant right-wing organization,

known as "Grey Wolves", claimed they were supporting the state security

forces.

In December 1978 martial law was

imposed in 13 provinces in response to violent riots in the south-eastern

city of Kahrarnanmaras, during which over 100 people were killed. During

the nine months after the Kahramanmaras riots the govemment extended martial

law to cover 20 provinces. However, political violence and killings increased

in those areas under military rule.

Inside Mamak Military Prison in

Ankara. Thousands of people have been jailed for political offences since

1980, many of them solely because they exercised their right to freedom

of expression and most after unfair trials.

On 12 September 1980, Turkey's military

leaders seized power under General Kenan Evren. Martial law was extended

throughout the country. The generals abolished parliament, suspended the

Constitution and banned all political parties and trade unions, and most

other organizations. For the next three years the Turkish armed forces

ruled the country through the National Security Council.

Immediately after the coup, the

number of political killings decreased substantially. However, the level

of human rights abuses increased dramatically.

Tens of thousands of men and women

were taken into custody. More than 30,000 were jailed in the first four

months after the coup.

During the following years, Amnesty

International received thousands of allegations of torture including reports

of over 100 deaths as a result of torture.

Trade unionists were arrested en

masse. Fifty-two leading members of the Confederation of Progressive Trade

Unions (DISK)

Tanks patrol lstanbul 's deserted

streets after the 1980 military coup.@ Camera Pre

were seized immediately after the

coup. By the time the military court delivered its verdict in 1986, the

DISK trial had 1,477 defendants.

The DISK trial was one of many mass

trials that progressed ponderously through the military courts, presided

over by high-ranking officers of the Turkish armed forces. Most took years

to reach a verdict, and many of the defendants stayed in prison from the

day of their arrest. Some of these trials are still in progress.

People from most sectors of Turkish

society were put on trial, teachers for their lessons, writers for their

books, journalists for articles they had written, trade unionists for organizing

workers, Kurds for separatist activities, religious leaders for their sermons,

and students for attending seminars. Even lawyers have been arrested and

imprisoned for defending their clients.

In 1983 martial law restrictions

were eased. From May 1983 the military authorities allowed limited political

activity and this was followed by general elections in November.

Three parties were allowed to field candidates.

The conservative Motherland Party

(ANAP), led by Turgut Özal, won a majority of seats in the Grand National

Assembly of Turkey (TBMM), the parliament. Turgut Özal was appointed Prime

Minister. From December 1983 military rule was gradually withdrawn. It

was finally lifted throughout Turkey in July 1987.

Although Turkey returned to civilian

rule some five years ago, the government has failed to ensure that human

rights are protected. Political prisoners are still tried by military courts.

State security courts, intended to replace military justice, have failed

to give defendants a fair trial. Some have been sentenced to death after

unfair trials.

Torture continues, despite Turkey

having signed and ratified the United Nations Convention against Torture

and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and

the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading

Treatment or Punishment.

Although in recent years fewer people

have been detained than in the years immediately after the coup, Amnesty

International believes that any person who is detained on political grounds

is in great danger of being tortured.

Mustafa Dilmen, the president of

the Mersin branch of the glass-workers' trade union, Kristal-ls, was detained

at the beginning of June 1988. He was interrogated at Ankara Police Headquarters

and held incommunicado for more than a week. After his release he

made the following statement:

"When I was taken to the capital,

Ankara, I felt quite relaxed. I knew that the anti-torture convention had

become law. Parliament had ratified it.

"However I could not perceive any

significant change."

The trade union president said he

had been subjected to various forms of torture. He concluded:

"I believe that there are certain

things one human being should not do to another. Torture is first among

these. It is my wish that torture, the disgrace of humanity, will be prevented

and that those who carry it out do not get away with it."

Mustafa Dilmen, tortured in June

1988.

The Turkish security forces

Most allegations of torture cite

two branches of the Turkish police: the political police and the department

for capital offences and violent crimes.

The political police include special

teams trained to deal with particular political organizations. These teams

have extended powers which, for example, allow them to follow suspects

beyond the borders of the province in which they are based. There have

been frequent allegations that some members of these special teams are

trained as torturers.

In rural areas, police duties are

carried out by the gendarmerie, which is part of the military structure:

members of the gendarmerie serve as professionals or conscripts, as in

the army. They have also been accused of torture.

Allegations of torture are not restricted

to the official police force: the National Intelligence Organization (MIT)

has also been named in torture allegations. MIT's operations are shrouded

in secrecy.

The police force in Turkey increased

significantly between 1984 and 1987 - by 50 per cent according to the Turkish

newspaper Cumhuriyet- far outstripping the growth of the population as

a whole. This is also reflected in the large increase in the number of

police premises: an 89 per cent increase in the number of police headquarters

and a 60 per cent increase in the number of police stations.

Many new prisons have also been

built. Since 1982 the total number of prisons has been increased to 644

and their capacity from 55,000 to over 80,000 prisoners.

If you take this as Page 001 of the

Briefing you may now continue with Page 002 at the

slide

show.

Helmut Oberdiek * 18.9.1947 — † 27.4.2016

Helmut Oberdiek * 18.9.1947 — † 27.4.2016 Library of HO from HF in HH

Library of HO from HF in HH